Franciscus

Franciscus

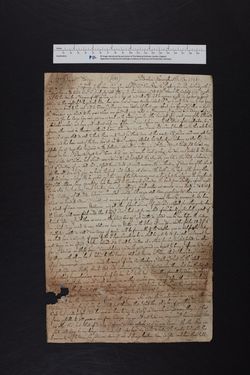

The ill-fated voyage of the ship Franciscus of Hamburg resulted in the survival of some of the most extraordinary letters and papers in the Prize Papers collection. The ship began its journey in the port of La Orotava, Tenerife in early 1744, where its crew took on casks of local Canarian wines, bundles of dyewoods harvested in Campeche, Mexico, along with sacks filled with pieces of eight. This cargo was typical of the Canary Islands and reflects the archipelago’s place in an emerging global system of trade. Dyewoods (Haematoxylum campechianum) were commonly harvested in Campeche, Mexico by unfree or enslaved people and almost all of the silver used for pieces of eight came from a mine in Potosí (in Bolivia, today) where indigenous people toiled under a forced labour regime known as the Mit'a system. Tenerife served as a node linking these spoils from the Spanish Empire with a range of European markets and in the case of the Franciscus, it carried these goods to Hamburg.

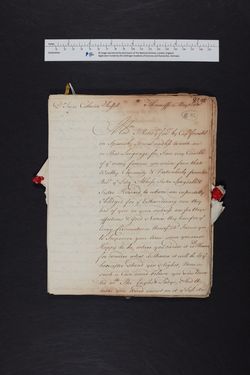

For the ship’s German captain, Christian Lourentzen his concern was with the risky voyage north, as he had to make it to Hamburg while evading capture by privateers or naval squadrons, as Europe was then embroiled in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). The situation of the Franciscus was tenuous, as while it was based in the neutral port of Hamburg, it carried cargo belonging to people who were technically on opposing “sides” of the war, including traders from Ireland, Spain and France. Any privateer or naval vessel that stopped the Franciscus on its voyage may then have grounds to seize it for carrying enemy cargo, making it was a high risk, high return venture for investors scattered across Europe.

The Franciscus sailed from Tenerife on 20 May 1744 and then made its way north along the Atlantic seaboard during the following weeks. On 5 June Lourentzen and his crew had a close shave when they were stopped by a fleet of French warships on the coast of Brittany. French sailors then ransacked the ship, hoping to find papers that proved the Franciscus carried English goods, but fortunately for Lourentzen they were called away by orders to sail for Martinique. The crew’s luck then ran out on 23 June, when the ship was ambushed and seized off Beachy Head on the coast of Kent by a British privateer, which then carried the Franciscus into Dover. The papers of the Franciscus were then divided into bundles and sent as evidence to the High Court of Admiralty’s Prize Court in London, which arbitrated wartime captures. The Franciscus and its lading were then eventually condemned and granted to the crew of the British privateer as legitimate “prize”.

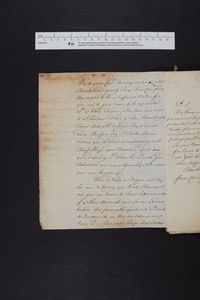

The papers from the Franciscus that survive include materials in English, French, German, Spanish and Dutch, many of which are mail-in-transit, and they offer a unique view of the people that sustained links between the Spanish Empire and Northern Europe during the eighteenth century, many of whom were Irish and English Catholics.

Discover HCA 32/111A: Franciscus and HCA 32/111B in TNA Discovery

Browse the documents in the Prize Papers Portal

The Network of John Blake of Ballinakill

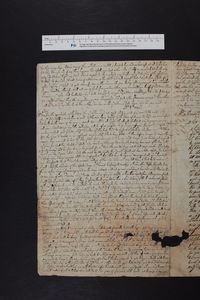

By far the most common name to occur in the collection is John Blake, an Irish Catholic merchant originally from Ballinakill, Co. Galway and the owner of perhaps half of the cargo on the Franciscus. Blake was a longtime resident of Santa Cruz, Tenerife by 1744, where he served as a contact for European merchants seeking to trade into the Spanish Empire and the Mediterranean. Blake sent dozens of letters on the ship that were strictly business, to communicate with the many investors who funded the voyage of the Franciscus. Written in English, French, Spanish and Dutch, they show Blake’s commercial network that spanned from Tenerife to Hamburg, London, Jamaica, Martinique and South Carolina.

A few people stand out in his correspondence and show the varied profiles of the investors in the Franciscus. His main partners were Joachim Heusch and Joachim Kähler, the ship’s owners who were both wealthy merchants in Hamburg. Blake’s links to French investors were run through a Dunkirk trader addressed as ‘the widow Benezet’, suggesting she assumed the business of her merchant husband after his death (a common practice). His London-based partners were invariably Irish merchants, especially Patrick Madan, who linked Blake to trading connections in British colonies across the Americas.

Blake was by no means unique, as Irish Catholics commonly served as commercial intermediaries in Spanish ports as early as the 1500s. Many Irish traders fled the warfare and vanishing commercial opportunities for Catholics in Ireland that followed as the English government tightened their grip on the island and some developed a niche in Spanish ports, in part because they could easily converse and trade with Northern Europeans. They were also of unquestionable Catholic descent, a significant detail in the Spanish imperial system, which often forbade those with recent Jewish, Protestant or Islamic ancestry from trade. A letter from the French trader Jean Pozlieu testified to the success of Irish merchants in the Canaries, as he claimed that by 1744 the Irish were the largest community of foreign merchants on the island, closely followed by the Dutch and the Genoese.

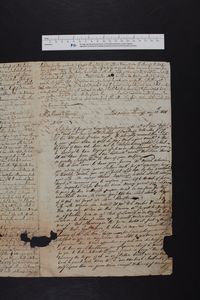

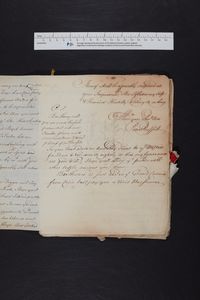

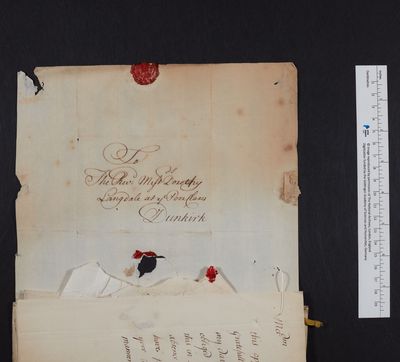

The Education of Catherine Russell

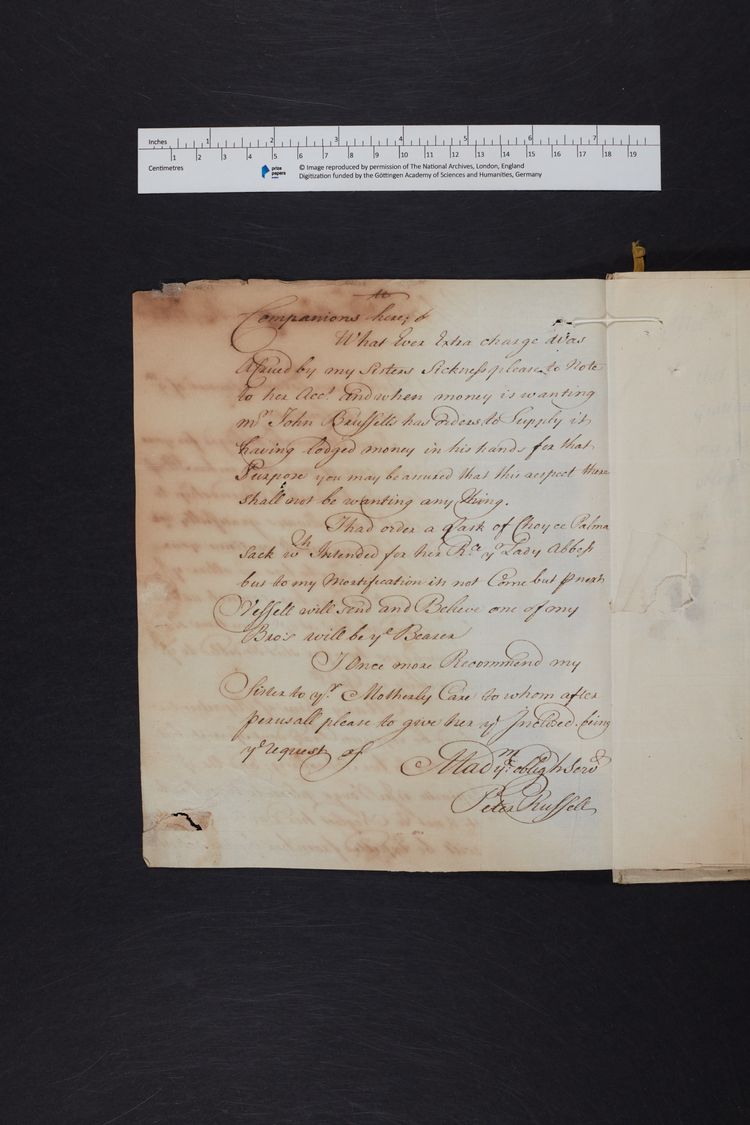

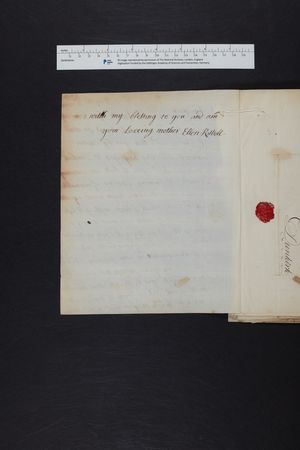

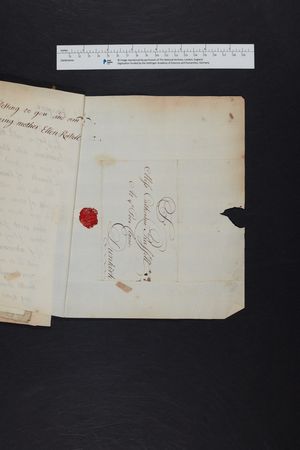

One particular bundle of letters was intended for Catherine Russell, a young woman living at a convent of English nuns at Douai, near Dunkirk. Catherine came from a family of wealthy English Catholics based in Santa Cruz, Tenerife and she had been sent to Douai to be educated by the nuns, as was common for women of a higher social status. The town’s religious institutions were considered to be prestigious and an education there would not have come cheap. Given that Catholicism remained illegal in England, this was also an exile religious community and such communities Douai tended to have links with the Jacobite Court at Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

The letters were sent by Catherine’s family and convey stern expectation rather than affection. Her mother entreated her to ‘cause no disorder there’, while her older brother instructed her to ‘mind your leaning with cheerfulness’. A separate letter from her father to the Abbess at Douai who was overseeing Catherine’s education implored that she ‘keep her to her learning’ and not to ‘neglect her dancing as such will be expected from her by her companions here [Tenerife]’. These sentiments remind us that while it was a privilege to be formally educated in this period, much of its purpose was to uphold familial reputation and, in this case, affirm the family’s high status.

Some affection can be detected in the gifts that her family members sent to her on the Franciscus. They included ‘2 barrels of lemmons, 11 boxes of marmalat’ and a ‘box with sugar works [sculptures]’. These were products typical of the Canary Islands so perhaps would have reminded her of home while she stayed in the cold north.

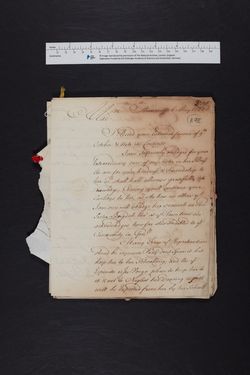

John MacCarrick: Musician, Poet, Linguist

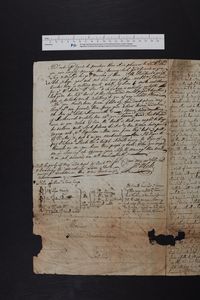

The Franciscus also had several passengers aboard when it was captured, one of whom was John MacCarrick, originally of Sligo. He was traveling to London where he was scheduled to be married and to settle there permanently, so it was perhaps fortunate form him that the ship was taken into Dover after capture, a port so close to his destination.

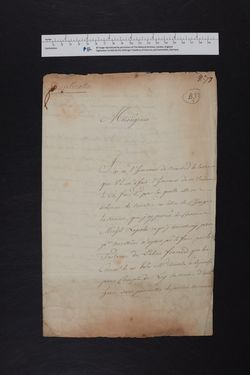

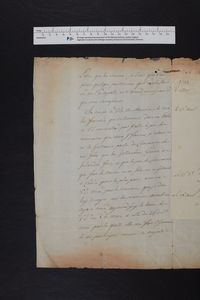

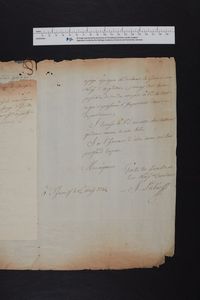

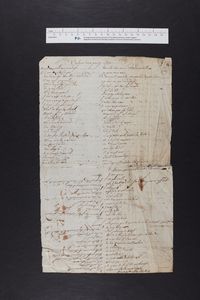

A handful of MacCarrick’s papers were confiscated at Dover and survived with the rest of the collection and they show the creative output of a mind bored by a long voyage at sea. The first example is a piece of paper where he was making notes and every inch of paper has been covered with text. On one side is love poetry, filled with the common chichés of this period. One verse reads: ‘away to yonder verdant field / to that delightfull grove / plantid by venus’ hand to yeild / ye shaming ards of love’. The remainder of the page consists of sentences written in both Spanish and English, where MacCarrick was practicing his handwriting. Turning over, he had compiled a list of phrases translated from English to French that he, an eighteenth century man, thought would be valuable for women. They include lines such as ‘I was agoing to your house – J’allois chez vous’ and ‘is he rich? – Est-il riche?’.

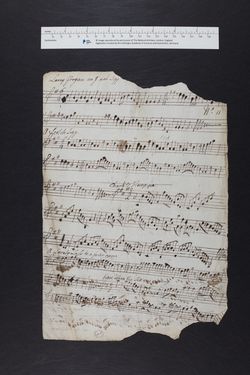

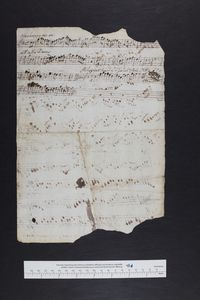

MacCarrick was also recording snatches of music from memories and noting them down. This set of very rough music manuscript is actually an extremely rare example of how music was transmitted on a popular level, with melodies recalled from memory, noted down and transformed by individuals. They include the tune ‘T'was When the Sea was Roaring’, often attributed to George Frideric Handel and another ‘A Lovely Lass to a Friar Came’ from the Beggar’s Opera by John Gay. The manuscript brings to mind MacCarrick singing or playing the fiddle on deck and recording the music from memory.

Conclusion

These are just a few examples of the enormous variety of material that survives from the Franciscus. Other records include the correspondence of nuns at the monastery of Santa Catalina at San Cristobal de La Laguna, family letters in German and papers relating to the life of the Canarian painter Domingo Sánchez Carmona. They are an invaluable addition to the Prize Papers Portal that will be of interest to researchers working in many different languages and disciplines.

by Dr Oliver Finnegan

Prize Papers Record Specialist, The National Archives, UK

Contact: oliver.Finnegan@nationalarchives.gov.uk

Daniel Fleisch

Database and editorial support

Contact: daniel.fleisch@uni-oldenburg.de

Lena Katharina Adler

Student research assistant

Credit: Franciscus, TNA, HCA 32/111A, Photo: Maria Cardamone, Mustapha Ousellam, Prize Papers Project. © Images reproduced by permission of The National Archives, London, England.