La Ninfa

La Ninfa

The Nuestra Señora de los Remedios, also known as La Ninfa, was a Spanish merchant ship that covered the route between Cádiz and Veracruz in 1747. It carried different goods (wines and liquors, steel, quicksilver, clothes…) both belonging to merchants and to the Spanish crown, as well as passengers sailing to Havana, Veracruz, Buenos Aires, and other destinations in the Spanish Americas. It also transported many letters, as well as the personal archives of some of its crew members and passengers.

The Ninfa was a “registry ship”, an innovation introduced by the Spanish crown during the Anglo-Spanish war of 1739-1748 (also known as the “War of Jenkins’ Ear” or “Guerra del Asiento”), one of the different conflicts that became ingrained in the War of Austrian Succession. Traditionally, the Transatlantic route between mainland Spain and the American possessions of the Crown had been carried out by a system of fleets, in which convoys of merchant vessels were escorted by warships. Aware of their naval inferiority during the war with the British, and with the aim of preventing loses, the Spanish decided to temporarily suspend the system of fleets and allow individual ships to ply the routes between peninsular Spain, the Americas, and the Philippines. The experiment also made it possible to test how colonial markets would react to a more flexible commercial system. During the nine years of the Anglo-Spanish war, 120 registry ships sailed to New Spain and the rest of America, although more than half were lost. These ships, nevertheless, managed to keep the markets open and ensured the flow of goods and people, despite the threat posed by the British Navy and privateers.

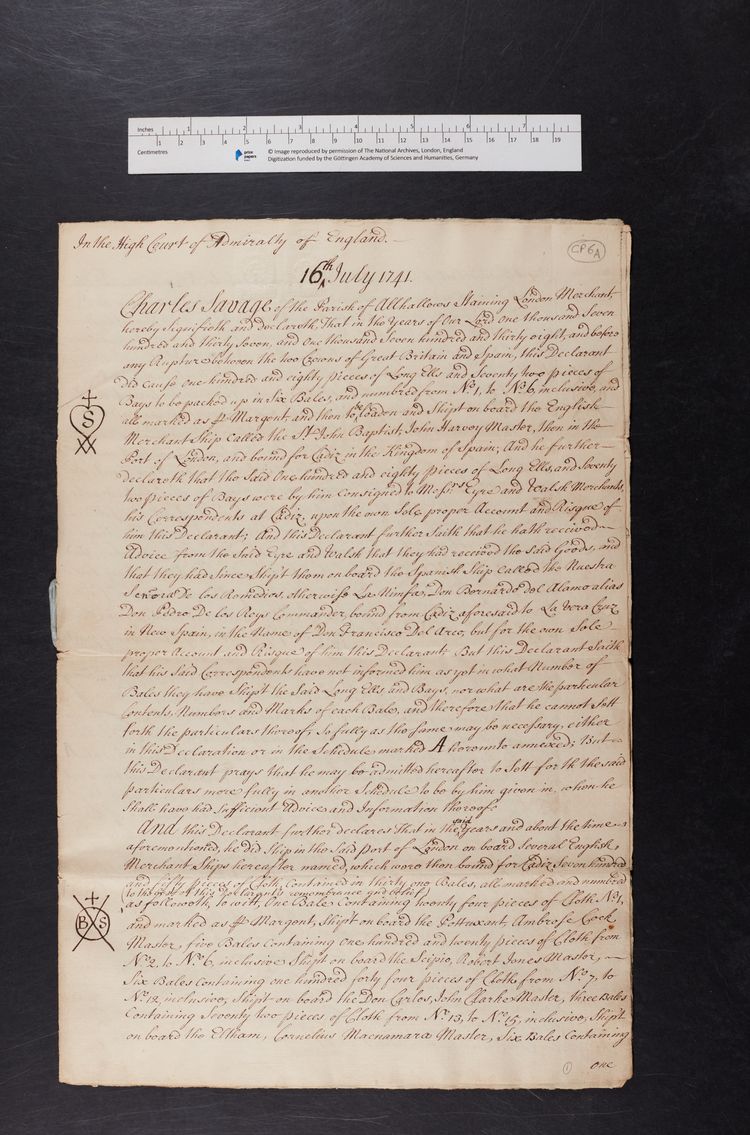

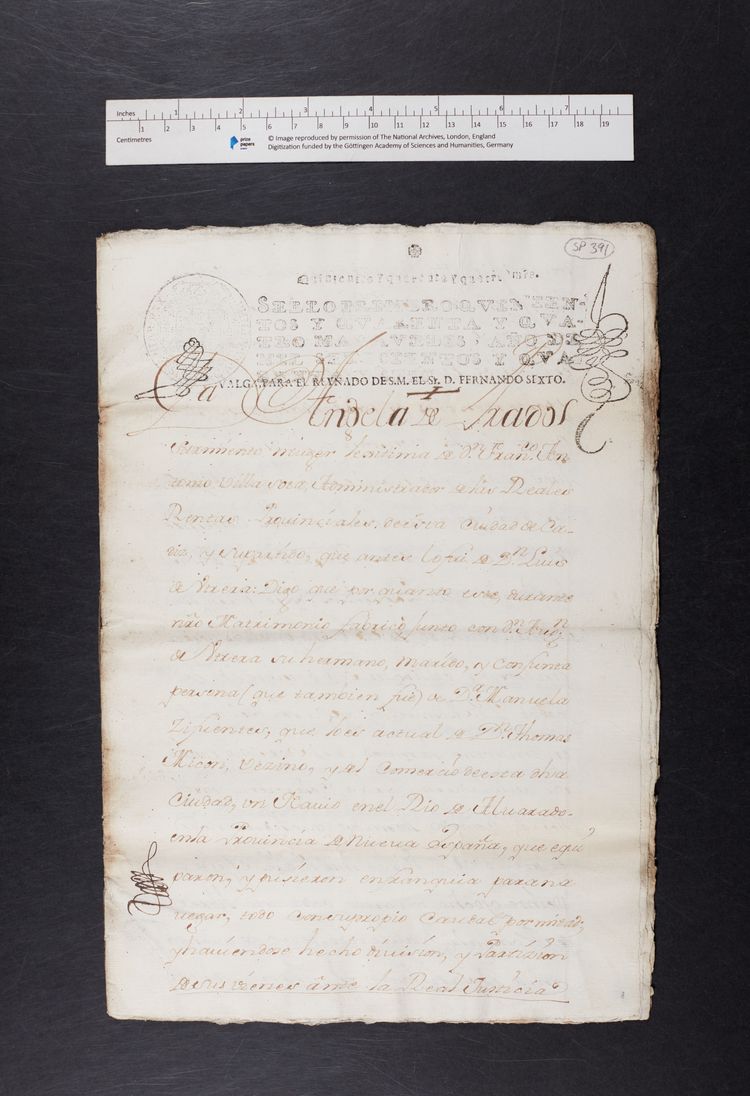

La Ninfa had already travelled to Veracruz in the past. The documents at the Prize Papers Collection (CP5-9) offer evidence of at least a previous journey undertaken in 1741, in which English merchants had used Spanish proxy names to ship their cargo. This practice was not unusual, especially in times of peace and during the first stages of the Anglo-Spanish war. In theory, the Spanish crown controlled trade with the Americas very tightly through a strict monopoly by which only Spanish merchants could ship their goods to Americas. In practice, fraud and contraband were widespread, and trading companies from Britain, the Netherlands, France, and other countries participated in the American trade thanks to partnerships and collaborations with their Spanish counterparts. The outbreak of the War in 1739 caused serious damage to the interests of English merchants operating in Cádiz and Sevilla as well as to their Spanish partners. English traders that wanted to keep operating within the Spanish Atlantic had to find alternative ways to maintain their activity. The ownership documents of La Ninfa (SP391) can be useful for historians of business and trade interested in transnational networks and partnerships.

La Ninfa transported a wide collection of documents, including abundant correspondence and mail in transit from mainland Spain to the Americas. These texts offer a privileged glimpse into the daily lives, emotions, migratory networks, and commercial practices of people from all social backgrounds and from different parts of the Spanish empire. Some of the letters are related to the same people and allow us to partially disentangle complex networks of kinship and trust between both shores of the Atlantic. Many others are full of precious information about the quotidian experiences and feelings from families of humble backgrounds.

Researchers and curious individuals interested in migration, emotions, labour, gender, family life, seafaring, trade, social history, religion, and popular perceptions of politics, among other topics, will enjoy reading the sources present on La Ninfa. Some of them have already been referenced by historians: Xabier Lamikiz used some of the documents of La Ninfaand other ships on the Prize Papers collection to reconstruct the migratory patterns, interactions and relations among Basque merchants and migrants in mainland Spain and the Americas. One of the letters on La Ninfa contains a note on the margin written in Basque, a very “important piece of evidence” since the Basque language in the Eighteenth century was mostly oral. (See Xabier Lamikiz, Trade and trust in the Eighteenth Century, 121-126)

Discover HCA 32/134/7: La Ninfa in TNA Discovery

Browse the documents in the Prize Papers Portal

The captors (and a monkey pet)

In February 1747, as it was leaving the Atlantic coasts of the Iberian Peninsula, La Ninfa was captured without offering resistance by the British privateer squadron The Royal Family, led by commodore George Walker. Walker’s squadron was very active in the final stages of the war, capturing many of the Spanish ships present in the Prize Papers Collection. However, Walker would face bankruptcy and imprisonment at the end of the war as a result of the costly chase and capture of Spanish warship El Glorioso, which produced more losses than gains. The capture of La Ninfa was one of his last profitable ventures. La Ninfa is mentioned on The Voyages and Cruises of Commodore Walker during the Spanish and French Wars, an embellished biographical account of Walker’s privateer career published in 1760 as an attempt to clear his name. There are several anecdotes and stories related to the ship on the biography, although their credibility is open to interpretation.

One of these stories features some wealthy Spanish passengers who had already been captured by Walker on the ship El Buen Consejo and were taken again on La Ninfa. When they found themselves again prisoner of Walker, they welcomed their former captors and joked about their fate, which seemed to make them meet again and again. The author of Walker’s biography claims that the commodore respected the personal belongings of their civilian captives, and that he was particularly fond of the Spanish. As a token of gratitude and appreciation for not stealing her jewels and allowing wealthy passengers to enjoy fine wines and meals, one of the passengers of El Buen Consejo, an unnamed Spanish lady, gifted Walker her lap dog, a cocker spaniel. Back on his ship, Walkers’ other pet, “a Chinese monkey of great humour and capacity,” became jealous and attacked the dog, giving it a beating that caused its death after two days. This worried Walker, who was expecting a visit by the lady in a few days and did not know how to avoid the embarrassment. He consulted the Spanish prisoners he had on board, and they advised him to give the monkey, Pug, as a present to the lady. One of the sailors thought stuffing the dead Alexander was also a good idea. The surgeon of the ship enthusiastically agreed and offered to do the task himself, and so the Spanish lady received both a monkey and a stuffed dog. According to the biography, this lady was also on board of La Ninfa so, when the ship was intercepted, the commodore and his former monkey were reunited. Unfortunately, there are no references to the monkey in the documents of La Ninfapreserved on the Prize Papers collection, so the story might have been a fabrication.

Excerpts from The Voyages and Cruises of Commodore Walker during the Spanish and French Wars, 1760, making reference to La Ninfa:

The documents

The privateers were able to confiscate more than 500 documents from La Ninfa. A large section of them consists of mail in transit from different parts of mainland Spain to various locations in the Americas. There are also personal archives and correspondence that belonged to crew members and passengers, and which includes interesting and unusual documents, from official certificates to cooking recipes, as well as two poems.

One of the recurring themes on the documents of La Ninfa is migration. Besides official and unofficial migration documents, most of the letters on board La Ninfa were sent to migrants that lived in the Americas. The letters, which never reached its intended destination, are a testimony of how families and friends tried to maintain ties across the ocean. Some of the documents show that contacts and communication, even if complicated because of the war and the long distances, could be kept. Others, on the contrary, reflect the desperation of families that had not received news of their relatives on the other shore of the Atlantic in years, sometimes decades.

Migration documents

La Ninfa carried several passengers who had the intention to migrate to the Americas. Some of these passengers were wealthy and well-connected, others had more humble origins. The documents of La Ninfa show the different realities of Transatlantic migration, including some of the alternative strategies that prospective migrants followed to be able to depart from Cádiz.

Theoretically, migration from mainland Spain to America was strictly regulated. The Leyes de Indias (Laws of the Indies) dictated that only natives of the kingdoms of Spain could migrate and settle in the Spanish possessions. In order to travel to America, Spaniards needed to apply for a licence. Only people who satisfied the criteria (Spanish nationality, Catholic religion, absence of Jewish or Muslim ancestors, no negative judicial record, correct skin colour) were given permission to sail to America. In the eighteenth century, Spanish authorities were concerned about the demographic decline in the peninsula, and actively tried to limit migration to the Americas. Only public servants, clerics, encomenderos (landlords) with their servants, merchants and factors who had goods to sell and purchase, and close relatives of migrants already settled in the Americas were given permission to cross the Atlantic.

La Ninfa contains two examples of migration documents for people who fulfilled all criteria. SP404 was issued for Luís Laso de la Vega, who had been appointed mayor of the town of San Luís de Potosí in Mexico, and who travelled with his brother Bernardo and a servant. Their official passenger license is located in the Archivo de Indias in Seville and can be consulted online.

For women, obtaining official passenger licenses was more complicated. They had to demonstrate that they had a husband or a close relative in the Americas who had explicitly asked them to cross the sea and reunite for them. For this, they needed to show personal letters that were copied and certified by notaries. SP405 was issued for Magdalena Valiño, wife of Francisco Monllor, resident in Mexico and "Tallador Mayor" of the Real Casa de la Moneda. The document contains extracts from letters sent by Francisco Monllor. Magdalena and her two children, Ventura and Antonia, were given permission to travel to Mexico on La Ninfa. The money for the passage was lent by Manuel Azorín and was promised to be paid to the master of the ship by Magdalena or her husband once they arrived in Veracruz. The official license can also be found in the Archivo de Indias and can be consulted online.

Those who could not obtain a licence or pay the costs of the journey would find alternative ways, such as travelling as criados, servants or employees of another person, deserting from a ship on which they were employed once in the New World, or trying to slip on board as stowaways. One of the documents of La Ninfa, SP402, shows an alternative strategy to migrate legally yet irregularly: Juan Luis González, from Sevilla, obtained a passenger license for him and his brother. In the official document, which can be found at the Archivo de Indias in Seville.

Juan Luís González declared that he was a merchant who had some goods to sell in Veracruz. However, a document on La Ninfa (SP402, transcription below) shows that this was a fiction. The document is a declaration in which Juan Luís González declares that the goods he was supposed to carry and sell in Veracruz belonged in fact to Juan Manuel de Bonilla, master of the La Ninfa, who had made him the personal favour of declaring them as his so he could obtain his passenger license. This document is an exceptional testimony of how migration regulations could be circumvented, and how ship masters and passengers collaborated.

Transcription of SP402

“Digo yo, don Juan Luis González, vecino de Sevilla y residente en este, que en el registro del navío nombrado Nuestra Señora de los Remedios, tiene cargado don Juan Manuel de Bonilla, quarenta quintales de rejas de azar, en trezientas noventa y nuebe rejas; que son suias propias, y por hazerme favor y buena obra, para poder sacar mi lizenzia, a fin de pasar a los reynos de las Yndias, ha convenido que dha rejas bayan a mi nombre y consignación siéndolo cierto que no me pertenecen por ningún título. ni las admito y así lo declaro y lo firmo en Cádiz a 14 de Octubre de 1746”

Recommendation letters

On La Ninfa there were several recommendation letters. These documents were essential for prospective migrants who had no contacts overseas and who did not enjoy a comfortable economic position in Spain. They were usually written as brief letters and were meant to be delivered by the recommended person to a friend, relative, business partner or acquaintance of the writer of the letter. 0016 is a good example (transcription of 0016 below)

Transcription of 0016

“Hermano mío el dador de esta es persona de mi cariño por lo que te suplico le atiendas en lo que esté de tu parte. Tus hermanas y io estamos vuenos y para servirte y deseosos nos escribas a menudo.

En Burgos y la monja, estan vuenos y en Madrid también gozan de salud, espero no te olvides de lo que te tengo escrito en distintas ocasiones lo que no te repito aora por estar prosimos a salir los navíos. No te canso más. Dios te de muchos años.

Cádiz febrero 13 1747

Tu hermano que te estima

Lucas de Noriega Colosía

[PS] - Ya te he dicho que por hallarme ynabil, para bajar a la corte dejo de lograr empleo que pudiera sufrutar algunos alivios mes de el que sufruta el que oy tengo que es thte, de la Benta de Sevilla“

Manuel Gil de Linares was one of the passengers of La Ninfa that hoped to find a suitable job in Mexico as a clerk or secretary, since he was very good at “writing and counting”. It sems that he was not able to produce a passenger license, but nonetheless he was admitted on board of La Ninfa thanks to a personal request delivered to the master that mentioned that he was the nephew of Lorenzo Linares (SP360, transcription below)

Transcription of SP360

“Señor Capitán don Bernardo del Álamo, sírvase Vm de admitir abordo, al dador de este, que ha de pasar de buena Boya a la Veracruz. haga Vm que se le atienda que es sobrino de Don Lorenzo y [...] todo quanto se pueda. Cádiz 13 de Febrero de 1747”

Manuel Gil de Linares carried several letters of recommendation, most of them written by himself on behalf of others, like 0054. A couple of them were signed by his uncle, like 0074A and 0076A. Manuel’s uncle, Lorenzo Linares asked his friends and acquaintances to help his nephew, who had no other capital than his skills as clerk and accountant. If they could not provide him with a job, at least he hoped they would be able to offer him advice and guidance in Mexico.

Another example is a man called Benito del Campo Palacios. He also hoped to be able to find employment as a clerk or secretary. He carried two letters, written by himself on behalf of his protectors, P0106 and P0111.

Many migration networks were based on geographical ties. P0108 and P0114 were kept by a man called Juan del Hoyo Inguanzo and were addressed to people from his hometown, Cartagena, in the hopes that he would help him settle.

Sometimes, the recommendations were part of larger letters, like 0048 and 0049, two lengthy letters containing personal information, commentary on political affairs and advice for migrants, personally delivered by migrants hoping to be employed by the addressees.

Not all recommendations were written by wealthy or influential people. P0095 was sent by a woman named María to a friend of hers, her “compadre” José. She asked him to provide as much as help as possible to her godson Juan Lavado, who would carry the letter personally.

In other occasions, recommendation letters were addressed to people who did not personally know the sender. Additional precautions were taken to ensure that people carrying the letters were who they claimed to be, and to prove the identity of the senders, especially when family ties were invoked. That was the case of Xabier del Castillo Ynguanzo, from San Vicente de la Barquera. He carried a recommendation letter written for him by María Josepha de Cosío Mier, who was the wife of his deceased cousin (P0115). María Josepha recommended him to his cousin Joseph de Cosío Miranda y Zúñiga, whom she did not personally know. To prove her identity, María attached the last letter she had received from his uncle, Joseph’s father (P0116), an interesting document that incidentally shows several examples of transoceanic family ties in the Spanish Empire, from Mexico to Philippines. Additionally, and to further demonstrate his identity, Xabier del Castillo carried a copy of his baptismal certificate (P0117).

Letters

The Ninfa carried more than 150 letters. The majority are loose letters, but some of them were sent by the same people or were directed to the same persons. Most of these letters are personal, although there are some others related to business and commerce. Most of the letters on board on La Ninfa were sent from Spain to relatives in the Americas. Some of them were kept by crew members or passengers, others were just mail in transit carried by the ship. Many were written by women from all social backgrounds. Some of them, written on expensive paper and with elegant calligraphy, were addressed to prominent members of colonial society, and included information about commercial and political affairs, as well as detailed descriptions of personal affairs. Others were written by less privileged individuals, sometimes on their behalf since they were illiterate. These tend to be shorter, with a harsher handwriting style, but they are also vivid and full of emotions.

This collection will be appealing not only to historians of emotions, gender, family, and migration, but also to any person with a general curiosity on the intimate lives of common people in the Eighteenth century. Here we highlight some examples related to family life, but the collection includes many more, covering a wide range of topics, from religion to military and political rumours:

From wives to husbands

Many of the letters on the Ninfa were written by women who were trying to reach out to their husbands. Some of them are full of love, nostalgia, and good wishes. Some others, on the contrary, reveal spite and resentment because the addressees seem to have abandoned their families and left them in precarious situations. Migrants and men who worked in the sea, either as ship crews or merchants, spent long periods apart from their families. Some of them kept constant communication with their families, some others seemed to have been less attentive. In any case, war complicated things, since many letters never reached their intended destination, as it is the case with most of those who were captured on La Ninfa.

La Ninfa carried letters to different parts of the Spanish Atlantic. There are two letters from women from Triana to their husbands, who were in Havana. Eusebia Milo was the wife of Pedro León, a sailor in the Spanish Royal Navy stationed in Havana. She asks his husband why he has not sent letters home and informs him of the situation of her family (0086A). María Gómez asks her husband Salvador Polo, who was on a ship called El Dragón Nuevo, to return as soon as possible because she is working too much; she also sends memories from their children and relatives and friends (0087A).

Although the letters in La Ninfa tend to have a bitter tone, there are also examples of affectionate letters. Rita Montero, from Cádiz, wrote a letter (0027) to her husband Joseph de la Puente. She informs him of how she gave birth to a baby girl. She also addresses their son at the end of the letter; it seems father and son had travelled together. Other moving example is the letter from Ana Herrera to her husband Julio Salvador (0012), in which she informs about her health, some changes in her life, the illness of their daughter and shares some news, including a reference to the ship La Begoña, which sank near Sanlúcar de Barrameda.

The captains’ wife

Bernardo del Álamo, captain of La Ninfa, kept a letter (P0030) written by his wife, María Maltés, shortly after his departure from Seville. She expresses her love and her worries about the weather, and tells how their little daughter constantly calls and searches for her father:

“Bernardo mio y mui querido de mi corazón y dueño de mi vida, resiví tu carta q fue para mí de mucho gusto porque me dises llegastes bueno el miercoles que yo estaba con algun cuidado por la mudanza del tiempo desde el lunes a mediodia q enpeso a llover aller viernes no seso en todo el día de llover aguaseros q oi a manesido el rio por ensima del muelle y los barcos se an amarado mui vien porque el tiempo va despasio la caja la llevara romero cuando el tiempo lo permita las novedades de casa son las mismas q tu dejastes yo estoi vien mala pues me falto todo mi consuelo y mi descanso no te digo mas en este asunto si no q obre Dios y que se haga su santa voluntad todos estan buenos en casa bernardilla dise con mucho enfados y gritos para q se fue padre para q se fue y te busca por la casa, y en la cama con esto me renueva a mi mi pena parese que quiere Dios q supla esta criatura la voluntad q le falta a el que engendramos Dios lo favoreca en lo que me dises del santo Cristo para el padre pedro este q esta en casa no sirve para es porque esta ronpido y mui viejo Conque si te parese mercaselo que puedeque lo quiera de tu mano no tengo otra cosa q desirte pues vien puedes considerar cual estara mi corason asi como esta te lo ynvio pues tullo y de Dios es y ni en ti ni en Dios hallo consuelo pues te aseguro q desde el domingo q te apartastes de mi no tengo ystante de gusto q no se en que vendra a para parar ya

Dios te guarde muchos años

Sevilla y enero 19 de 1747 tu esposa q mas te estima y ver desea

María Maltés del Álamo

Mi querido esposo Bernardo del Alamo mi dueño

[PS] – mean dicho que se enbarca bonilla dime si es verda”

“You left me like a flower in the frost”

Some texts mix affection and longing, like a letter from a woman called Ana Hernández to her Manuel Robles (P0086). Ana Hernández misses her husband and makes explicit references to her physical absence and the fact that he left when her body was at its best moment. She claims not to want anything but her husbands’ return, and hopes that her brother Juan Francisco, who carries the letter, finds him:

“Hesposo y muy querido mio me alegrare goses salud la mía para lo que me quicieras mandar que lo are como es mi obligasion

Hesposo de mis carisimas entrañas te he de ver el fabor que amas q la estimasion en que te tengo ya no te suplico que me escribas sino que tu persona sea el portador pues sabes que por ystantes te estoy aguardando no deseando medios sino el Cuerpo son salud mientras Dios la da Pues sabes que de mi no tienes queja ninguna solo si sabes que me dejaste como la flor en la escarcha y en el megor tiempo de gozarnos me beo tan ausente de tu presencia que no puede ser mas y asi bente quanto antes que solo con tu bista deseo salud espiritual y corporal no quiciera molestarte tanto con razones que si loable fuera si como soy mujer fuera onbre o resueltalo son muchas ya fuera en busca tuya tu cuñado Juan Francisco y ba en busca tuya y no que solo fortuna por algunos y conbenientes el pasar de Caiz no te canso mas sino que Dios te me guarde los años (...)“

“It is more likely to be lack of will...”

Often, husbands abandoned or neglected their families in Spain, and their wives tried to send them letters to remind them of their responsibilities. A certain Juan de Munoa, from the Basque country, travelled on La Ninfa and kept a letter written by her wife, Bernarda Catán. She complained about her husband’s absence, and asked him to come back as soon as possible, or at least to send letters more often. (P0040)

“Amado y querido hesposo de mi maior consuelo será el que te mantengas con salud que te la deseo con afecto beneficio que gozo en compañía de mi amada madre para servirte. Por no dejar ocasión de escribirte hago estas dos letras por dirección de don Miguel de Hercurechea aunque con aunque con el sentimiento de ygnorar tu paradero por ber si por alguna via descubro donde paras para poder escribirte con mas seguridad y consuelo el que me falta en tantos años cuantos a que carezco de tus cartas quiera Dios no ay sido falta de salud que para mi sería lo más sensible pero discurro mas sera falta de voluntad que el que la tiene aun del cabo del mundo encuentra por dónde escribir y asi te suplico que no seas tan omiso en dar noticia de tu persona como el que agas dilijenzia de restituirte cuanto antes a mi compañía para mi consuelo y alivio de mis trabajos y cumplimiento de tu obligazion que así se lo pido a Dios quien se sirbio llevar a tus padres para si sin acordarse de ti mas que si no fueras como te lo tengo escrito en otras antecedentes

Como también mis trabajos los que padezco bastante crezidos como lo puedes considerar en una tan larga ausenzia y pocas y ninguna conbeniencia rastrada en un barco desnuda y anbrienta con mi pobre madre que la contemplo mujer de un hombre de forma y verla en tanta indecenzia que se me cae la cara sin que ceca la pobre de pedir a Dios te de salud y te traiga con bien yo como mas ynteresada no me olbido en esta dilijencia dejándote dejandolo todo en manos del Altísimo Dios quien te guíe y gobierne y te guarde de todo mal

Mi madre se encomienda de corazon como también tu hermana con todos mis parientes y tuios y con esto no soy mas larga y adiós que te guarde para mí consuelo

Pasaje y septiembre 30 del 1745

tu esposa que de corazón te quiere y verde sea

Bernarda Catan”

The fake widower

In a dramatic letter (P0110), a woman named María rapproaches her husband Félix de Ceballos not only not having written since his departure and not having sent any money home, but also having told an acquittance that he was a widower.

“Hesposo después de desear tus aumentos de salud, quisiera gozaras en ti los auxilios de grazia que son los fines a que debe aspirar todo christiano; mas beo en ti tales descuidos que temo tu desgracia, Pues sabes ha 21 [?] que saliste de esta tierra y sabes también noas echo casso alguno de mi ni de tus olvidadas hijas; abiendo tan grande obligación para ello; y no abiendo motivo por nuestra parte, pues hemos bibido como nos toca de obligación sin la mas leve sospecha sujetas a trabajo para poder sustentarnos pues sabes que la necesidad suele ser acreedora de muchas liviandades. Mas espero en el todopoderoso que no nos dará lugar a cossa que toque en nuestro punto y asi te suplico por dios que lo dispongas de modo que puedas servirlas de algún alivio que para mi vendrá acaso tarde pero en María Santísima espero el verte antes de pasar de esta tan penosa vida a los eternos descansos; y deseo tenga esta mas dicha que las que tengo escriptas asta oy; pues abra un mes escribi una a ynstancias de don Plazido de Porras vezino de espoossa quien me dio noticias tuyas y me hubiera socorrido silo ubieras dado orden para ello aunque yo no lo demande cossa alguna = esta ba abierta e yncluida en las del Sr don Francisco de Baldibieso en quien me encomiendo con mil expresiones de deseo de servirle para que sepas no le digas lo que a don Plazido de que estabas biudo y por lo mismo y que aha por mi lo que en esta suplico, lo que espero de su grande gratitud y piadoso zelo que aunque fuera cierto debieras la obligación a tus hijas y el ciudado de que bibieran bien; no quisiera darte estos quebrantos mas ban de buen desseo de mandados títulos tienes bien merezidos = tus hijas y yo gozamos perfecta salud y rezibiras de mi y de ellas muchas memorias, los abrazos te los desean dar a boca que son los últimos deseos que tienen después del serbizio a Dios a que ruego te guarde los años de su voluntad de esta tuia y noble

24 de 1746 tu esposa María”

Three letters to Miguel Atocha

Miguel Atocha was a man from Sevilla who migrated to the Americas at some point. His absence caused many troubles in his family, not only because of the lack of economic support, which forced her wife and daughter to work as servants in the houses of rich people, but also because he was not there to raise his younger son, Miguelito, who was growing big and not respecting his mother and sister. His wife, Francisca, sent him a long letter (0029, transcription below) complaining about the fact that he had not written letters home in years, informing him of the many health problems that she and her daughter María endured, and sharing the news of the marriage of María to Joseph Hidalgo, a school master. There is also a letter from María (0030) and another one from Joseph Hidalgo (0007).

“Esposo y querido mío

Celebraré que estas cartas lleguen a tus manos y te halle con la perfecta salud que yo para mí deseo, la que me asiste ya puedes considerar la de tus hijos todos buenos =

Quisiera sabe qual es el motivo de haberte escrito treze cartas sin estas y de ninguna a ver tenido respuesta, quisiera saber si allá no ay papel o plumas o tinta para siquiera a ver escrito una, ya veo que es por falta no de lo dicho, ni de lugar, sino de mucho olvido que ya has hecho de toda tu familia, pues todos por acá tienen sus socorros, razón y sola yo soy la desgraciada, rodeada de tantas miserias qual no otro en este mundo, con más arrastes, y colmo de miserias el verme rodeada de estos dos pedazos que tanto tu te has apagado en el amor, pues tu hijo Miguel está hecho un hombre con más cuerpo que tú y también está en cueros, pues por acá no hay por donde trabajar ni ganar un ochavo, yo con mis muchas enfermedades tampoco puedo hacer cosa alguna, pues desde que saliste de esta tierra no he gozado de salud pues por diferentes veces he estado yo para irme a mi Camino y con más fuerza tres años a esta parte que estoy con una apostema en la garganta que ya puedes considerar y iendo y biniendo a un hospital y allá me dan las unciones para ponerme, y para las sangrías es menester buscar de limosna o que se ha de dar al Zirujano, Comer estoy aterida al que me quiere por Dios dar un bocado, pues ay días que no pruebo ni aun agua porque no tengo de donde sacarlo y verme tanto tiempo enferma sin poder salir aunque fuera a pedirlo de puerta en puerta = Ya si por Dios y la Virgen Santísima de la Encarnación te duelas de nosotros pues para ver a Dios es menester buscar una mano y una saya, y tu hijo quien le preste una capa para salir a Misa, y sobre esto puedes hechar las quentas, y luego que yo no puedo superarlo que como he dicho esta hecho un hombre y sin miedo de Padre haze lo que quiere, y sobre todo da providencia de el que yo como dize el Medico y Zirujano serán muy pocos mis días, tu Compadre Mena desde que murió su mujer se fundio, pues anda por la calle con una muleta pidiendo limisna y no te digo mas. De tu hija Maria estaba sirviendo que hasta eso que me aliviaba en alguna cosa también me lo quito Dios pues a poco tiempo de a ver estado en la Casa me mando el medico que la sacara porque no era para servir porque havia de enfermar como asi fue, haviendola traído a casa y puestose buena llegó a mi el Hijo de Estacio Hidalgo el playero y me dixo tenia hecho días havia concepto de casarse con ella que que respondia, a lo que le dixe tu estavas ausente y no podía yo disponer cosa alguna a lo que me dixo que ya ello savia mas viendo la mucha necesidad y que pasaba y no ser para ello aunque no lleva ningunos mayorazgos pero no obstante no falta, Dios a nadie y discurro que su padre de su merced no lo llevara a mal pues viendo estas razones y viéndola a ella en cueros, y ser el tal un mozo tan bien querido de todo el mundo, sin vicio, pues no bebe vino ni juega a naypes ni compañias lo acepte y se dispuso todo aunque no con todo el gusto cumplido pues faltabas tu pues el mismo lo decía, están en su casa solos tan querida de el que eso es no mas de para verlo, de su Padre Madre hermana y hermano de su parte no digo nada pues eso son desatinos el está de ayudanrte en la escuela de la Calle Larga, aguardando que aya coyuntura para quedarse con la escuela por ser el maestro de Mucha edad pario un Niño que fue el asombro de toda Triana y Sevilla vivió catorze meses y se murió día de Nuestra Señora del Rosario del año 1706 (1746?). Te envían ambos muchas memorias que desean verte y ya que no puede ser prompto desde allá les eches la Bendición para que Dios les de buen suceso las reziviras de tu hijo Miguel y mias a medida de tu deseo

Sevilla y Enero 22 de 1747

Tu esposa que mas te estima y ver desea, Francisca Muñoz

Esposo y querido mio Miguel Atocha“

Other family letters

Families tried to maintain their ties across the different corners of the Spanish empire. Parents sent memories to their children, reminded to the children to perform their religious duties, and delivered news like the death of relatives (0040). Sometimes mothers, like Josepha de la Peña from Triana, would ask their children for economic assistance (0008), while in other occasions they would complain about the complete absence of news from their children. The collection also includes some letters from children to their parents, like the one written by Manuel Linares —the person with the recommendation letters mentioned above—, to his father Benito (0013). Siblings informed each other of developments at home (0010), both happy, like births or marriages, and sad, like diseases or death (0041). They also requested instructions on how to conduct their business back home (0003). When they were taking care of their sibling’s children at home, they would send memories and descriptions of how children were growing (0072)

The letters from La Ninfa were written by people from very diverse social backgrounds. Here we offer a small selection of transcriptions, but the collection contains many more examples:

From father to son

There are several examples of letters written from fathers to their migrant children, like A letter (0073) from a certain Josphe (probably a misspelling of Joseph) de Jaldos (Galdós?) in Cádiz to his son, Antonio. The letter was meant to be delivered by Antonio’s brother, Juan. The tone of the father is strict and paternal, with a strong emphasis on the need not to abandon religious duties, though there are some expressions of appreciation.

“Querido y amado hixo de mucho gusto será para nosotros que tu querido hermano aya tenido al aribo a ese puerto y te aiga allado con la salud que nosotros deseamos en compañía de tus queridos amos nosotros a dios grasias gosamos dese bene ficio para lo que ustedes y tus amos nos mandan que lo aremos con todo afexto.

Querido hixo quiera dios que tengamos el consuelo de buenas notisias de que cumples con tu obligasion que siendo asi tendremos algun alibio de careser de tu bista tu madre sienpre que te escribo me en carga que no dexes las debosiones y el confesar siempre que tengas lugar con que asi puedes aselo parque cuando dios sea serbido traer a tu hermano Juan con felisidad nos de ese consuelo y eso lo as de aser no por mi no por tu madre ni por ninguno de los tuyos: sino por dios y por su madre y por los santos de tu debosion y de los nuestros y por el poquito de credito que dexastes en tu niñes nosea que aquello se pierda: en atenzion a nobedades no te partisipo nada tu ermana esta aguardando la ora de dios para su parto su maxestad se lo de como puede =

Resibirás infinitas memorias de tu querida madre y de tu querida ermana y de tu querida sobrina y mias las tomaras a tu medida asimismo las partisiparas a tu querido ermano y a tus queridos amos y les diras a sus merzedes que tengan esta por suya = tambien resibiras memorias de mi compadre tu padrino y de Don Carlos (?) tu maestro y de [folded] es cuanto se me ofrese pido y pedimios a dios es g. m. a

Cadis y febrero a 1 de 1747 a

tu padre que ber te desea Josphe (Joseph?) de Jaldos

Querido Hixo de mi Corazón Aantonio [sic] de Jaldos

[PS] querido yxo el mismo dia que aba escrito la presente tubimos el logro de aber resibido tu carta y con ella el tan felis logro de tu salud su maxestad te la continue no tengo que partisiparte nada solo te prebengo que no buelbas a escrebir de que es bueno el tener Conzexos que dios me dio el don de padre como asi dios te puede aser, no te digo mas y mira por ti, por mi no que dios es para todos y adios Asta que te bea“

From brother to brother

Some of the mail in transit carried by La Ninfa was addressed to Joseph de Villanueva, who seemed to enjoy a relatively privileged social position. There is a letter from his mother (0020) and from different family members, as well as one of his friends back home (0019). Here we offer a letter from his brother Juan Ignacio (0017)

“Hermano y querido M Joseph de Villanueva

Hermano, celebraré que ayas llegado a esos reynos con toda felicidad, sin aver encontrado embarcación enemiga, de lo que me alegraré mui mucho. Yo quedo bueno junto con Padre, Madre, el S. Don Domingo, Mariana, Hermana Juana, Juan Sánchez, el Ama y demás familia, quienes te se encomiendan con cariñoso afecto.

Hermano el Ama te estimó mucho el vestido de la niña el que no lo estrena hasta el día de San Blas, que es quando cumple un año, y ya tiene un diente y en todo el día para a hacer mil monerías.

Recivirás muchas memorias de mi señora doña Josepha Terron, de mi señora doña María Campomanes, del Señor Don Nicolás, de mi padrino y toda su familia, quienes te se encomiendan con cariñoso afecto.

No tengo ninguna noticia que participarte acerca de mascaras porque el tiempo no ha dado lugar a que salgan.

Le darás muchas memorias de parte de Madre, Mariana, hermana Juana, Juan Sánchez, mías, y de Pedro, a el señor Don Joaquín de Burgina, y a Simón, que no le escrivo por no tener lugar, y con esto cesso, y no de rogar a Dios te guarde los muchos años que puede y deso.

Sevilla, y enero 22 de 1747

Tu hermano que más te estima y ver desea

Juan Ignacio de Villanueva

[PS] El Padre Fray Benito, Fray Joseph, y el sacristán de los capuchinos, me dijeron que te enviara muchas memorias, y también el señor don Gerónimo, que no se olvidan de ti“

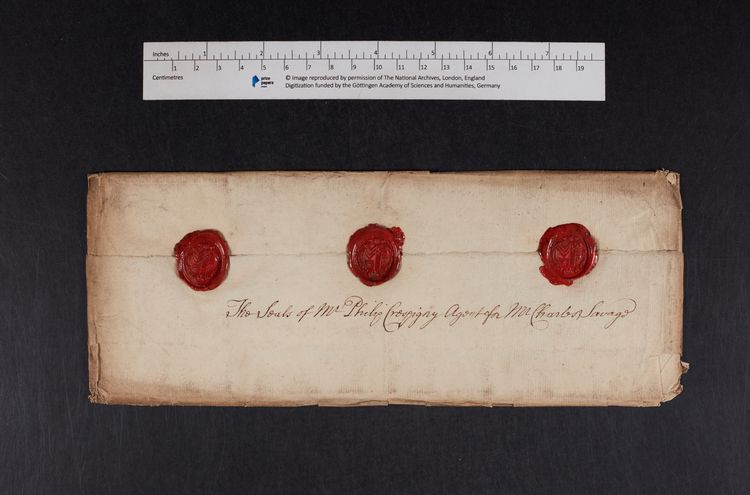

The personal archive of Francisco Álvarez de Guitian

Fransico Álvarez de Guitian was a merchant that operated between Spain and the Americas. He was probably on board of La Ninfa, since his personal archive (P54-P82) was confiscated when the ship was captured. His fortunes do not seem to have been affected gravely by the capture. Three years later, we find him as a ship master (see Archivo de Indias: Registros de ida a Veracruz and Registros de venida de Veracruz y San Juan de Ulúa) and in 1753 he secured a position as an official of the Casa de Contratación (see Archivo de Indias: Nombramiento: Francisco Alvarez Guitian). Nevertheless, he might have deeply lamented losing a collection of letters that may have held a sentimental value for him.

The letters in Francisco Álvarez de Guitian’s archive reveal many details about his private life, including a secret marriage with a woman, Francisca who seemed to be deeply in love with him, and a turbulent relationship with his son-in-law (to whom he owed money), and his daughter with, apparently, a different woman. Here, we show the first letter written by Francisca in chronological order (P0054), a very affectionate text with constant expressions of love and longing, together with some minor remarks about Francisco’s businesses.

Transcription of P0054

“Cádiz 23 de febrero de 1742

Amantísimo esposo y querido Panchito de mi corazón, si no fuera por este débil consuelo de escribirte con frecuencia no sé donde llevaría mi continua pena careciendo de tus cariñosos afectos y de tu compañía que yo aprecio tanto. Ya me va faltando la conformidad esposo mio, y todo es hacer propósito de no dejarte ir otra vez pues más te quiero a ti y estar contigo lo que me queda de vida que cuantas fortunas y riquezas puedas adquirir en tus viajes; para mi consuelo y satisfacción no hay otra que sobresalga a la de darte mil besitos y nunca sobreexcederá otra ambición en mí que la de pedirte que me quieras muchísimo, me desees mucho más, y aún con esto solo corresponderás a una parte del muchísimo y perfectísimo amor que te tengo. Panchito mío mucho me cuestas de pesar, y si dilatas tu buelta me allarás muerta del disgusto grandisimo de no verte, tú eres oy en dia y lo fuiste desde el instate que te amé el unico asumpto de mi pena y contento, y oy con tantas veras eres lo primero que ni aun la esperanza de lo segundo me puede consolar, infaliblemente todas las noches despues de acostada llamo con muchas lagrimas a mi Panchito, esposo de mi corazon, adonde esta mi marido de mi alma, por dicha mia no estoy casada con el pues que delito es desearle tanto, y porque el no me corresponde con este mismo deseo, y se viene a mis brazos amantisimo y seguro de que en ellos en todas fortunas y contratiempos a de ser adorado y querido mas que si hubiera nacido de lo mas vivo y perfecto de mi corazon! Panchito de mi vida, amante esposo de mis entrañas no es verdad que te he disfrutado poco; y que despues de casados ni aun un besito con libertad me diste, te acuerdas de tus males, de los mios, de que te pedi durmieses conmigo antes de irte, anda que cuando pienso que no me diste este gusto me entristezco mucho. En fin baste ya el referirte mis desconsuelos aunque para mi no tendrán fin hasta que tu mismo, tus abrazos, la realidad de tus cariños, el no faltar de mi lado (y de mi cama) desaparesca y aparte de mi tanto cuidado pesaroso.

Llegó la embarcasion del tocayo el dia 17 de este mes, con el deilatado viaje de siento y un dia, muy contento queda don Lorenzo, yo no porque pensava tener una cartita tuya mi alma, y he llorado mucho por verme sin la menor razón, su mujer queda buena y el niño y sumamente alegre de las notisias y remesas de su marido, mas lo estaria yo contigo, y como dios me conseda explicado con los guantes que le pediste, de novedades ay remito lo mas expesial, el Padre Torrivia se cartea con el Padre Roca y vienen las cartas bajo mi cuberta, yo creo que es en orden a cierta mitra.

Aora te pido por amor de Dios, por lo que más quieres esposo mio, que no dilates bolverte, asi por la notable falta que me hazes, como porque si lo miras bien no te co,biene hazer más gasto y te atrazaras muchisimo, bien bes la diferensia del presio en los generos respecto de los primeros, la diferencia de tu flete con los de otros, y la demora tan grande que aqui tuviste, no es razon que pues te expones a tanto riesgo hagas el viaje para otros, sirvate tu hermano para benzer las dificultades que an detenido a los otros despues de sus ferias y dame el consuelo esposo de mi corazon de verte breve si quieres que viva, yo me expongo gustosa a pasar el tormento de no tener carta tuya otros tres meses como se an pasado por tal que seas tu el portador.

Panchito mio, nada descuides en uo y otro asumpto que asi aré yo en el de pedir a Dios y a la santísima Virgen de Dolores por tu salud y felisida y breve le buelvo a hazer otra novena y en ella espero saver de ti esposo de mi alma y tener algun consuelo, con cuantas lagrimas escribo esto!

Es fixo qie don Feliz de Almera, tiene una embarcasion pero no saldrán tan presto, en viendolo le dire lo que sabes pues es cierto que estará quexoso de ti pero yo me dare toda la culpa disiendole que tu me lo dejaste encargado y que de cortedad o por falta de ocasion de allarlo solo o lo havia executado. El cavallero Miera salio para Madrid dias pasados

A Dios amantisimo esposo de mi corazon y de mi vida, a Dios que te guarde muchos años y que nos conseda su gracia para amarle y querernos en su amor santísimo muchisimo si mi alma tu verdadera, tu amantisima y querida esposa que te da mil besitos y abrazos de corazon,

Francisca Seviner”

Other documents

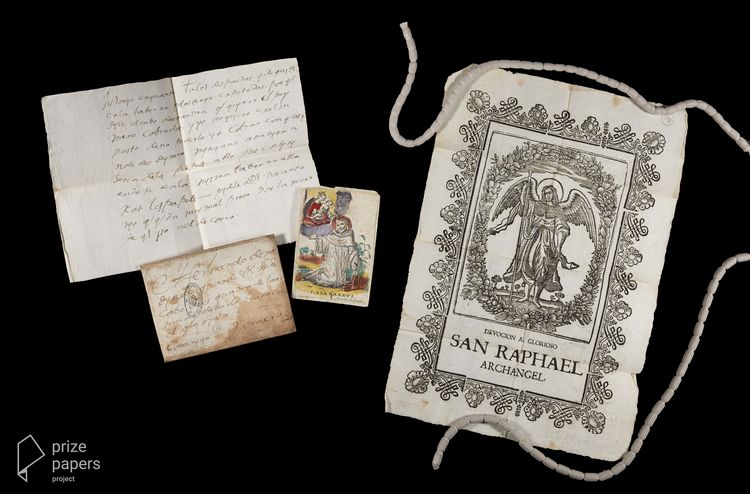

La Ninfa carried more than letters. Besides the documents related with the cargo, which will benefit historians of economy and trade, there are some other interesting sources. These documents shed light on different aspects of the daily life in the mid-Eighteenth century. Here, we have selected some pieces related with the journey of a friar to collect alms in Mexico, two poems, and two cooking recipes.

A religious journey

Francisco Hureña, also known as Francisco del Santísimo Sacramento, was a brother of the Discalced Carmelites of Sanlúcar de Barrameda, a coastal town located between Cádiz and Seville with a long history of Transatlantic ties. He was sent by the Prioress and Mother Superior of the convent of the Discalced Carmelites on a mission to collect alms in Mexico. The money would be used to repare the convent, which was experiencing a period of austerity.

The nuns produced several documents that were carried by brother Francisco. SP393 and SP395 are certificates that state that Francisco, a man who was not very educated or refined but who was good and loyal (“hombre aunque en su mediana estatura y en su exterior y conversación no el más leído y limado, de gran bondad y fidelidad”) was authorized by the convent to collect alms on its behalf. SP392 and SP394 are official petitions from the female leaders of the convent to the vicar of Veracruz and the archbishop of Mexico, respectively. SP393 is another certificate, signed by public notaries, proving the identity, position and religious profession of the nuns who signed the other documents.

Part of Francisco’s mission involved claiming a inheritance on behalf of one of the sisters of the convent called Juana María Manuela Clevería. SP399 is the baptismal certificate of Clevería, while SP400 is a power of attorney given to Francisco to claim the inheritance.

Cooking recipes

Among the many documents confiscated from La Ninfa, there are two pieces of paper containing cooking recipes. One of them (P082) belonged to the already mentioned Francisco Álvarez de Guitian, who seemed to have recycled a used address wrapper to note down four recipes, two in French and two in Spanish (transcription below):

“Escabeche, modo de hacerlo

Escamado el pescado, que para este modo, suele o debe ser lenguado, se le da una o dos cuchilladas [y se dalpresa moderadamente con sal menuda] en los costados y si es para transportar o embarcar, se fríe muy seco, y si para comer en casa, algo menos frito; se sienta en las vasijas o cazuelas en qué se debe guardar, previniendo que cada dos camas se le echa un poco de tomillo, laurel y orégano, un poco de sal menuda y una porción corta de todo género de especias molidas y mezcladas, si es para comer en casa se le echa, 1/3 de vino con dos de vinagre, y una m. O panillas de aceite, dejándolo tomar dos o 3 días la sazón y que estos ingredientes le dan; si es para enviar afuera no se le echa vino

Boronía

se parte en pedacitos la calabaza y berenjena, y después se pone a cocer lentamente con agua y sal hasta que esté muy blanda, entonces se echa en un plato y se le escurre muy bien el agua: hecho esto se echa en una cazuela el aceite correspondiente y en estando muy caliente se fríe en él cebolla menuda hasta que esté muy bien frita y cuando lo está se echan allí mismo los tomates mondados y cortados a pedacitos hasta que también están muy fritos; después se echa allí la calabaza y berenjena que estaba en el plato, y todo se trae un poco en aquel aceite después se masan las especias de [blank space] y un poquito de comino […] y se echan con un poco de agua en la cazuela para que todo hierva un poco hasta que se consuma el caldo y luego se llevan a la mesa.“

The other document (P121) is a small piece of paper with a recipe for hare:

“Sivete de liebre

Se haze cuartos y se lardea con tosino se echa sal y espesias vino y vinagre se deja amrinar dos oras con bastante sevolla y perexil [laurel?] y pan rallado y después se echa el todo en una olla y bien tapado se cose y si ay caldo se le echa un poco y de no con su aliño basta”

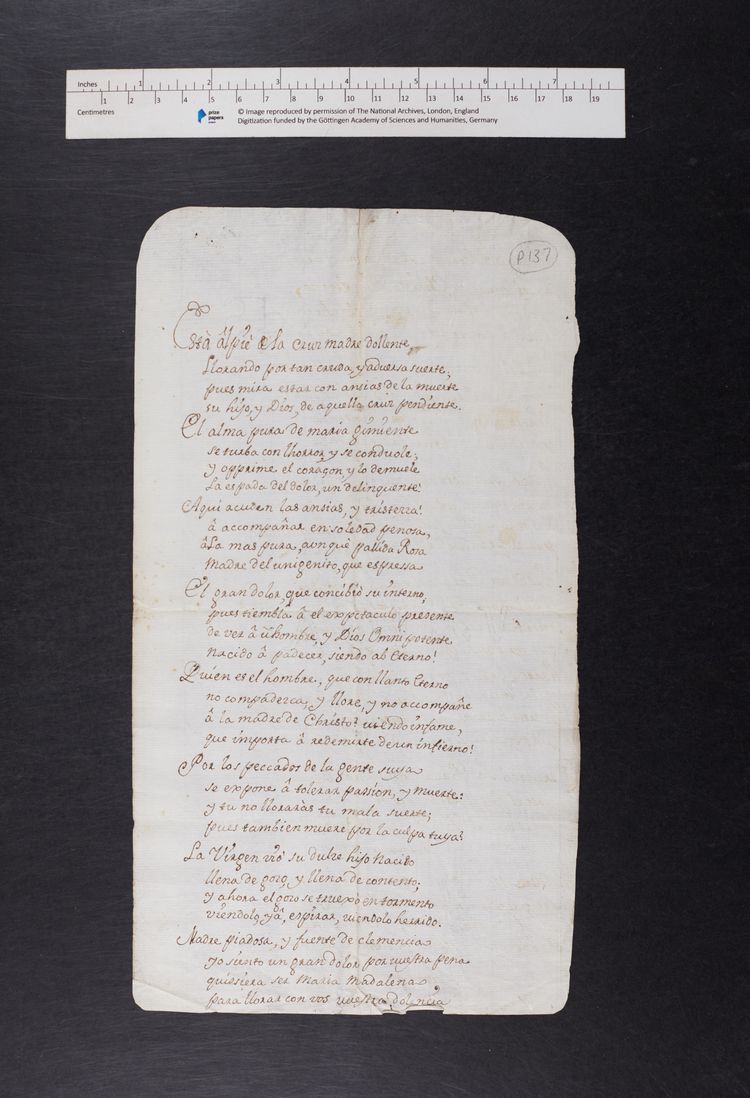

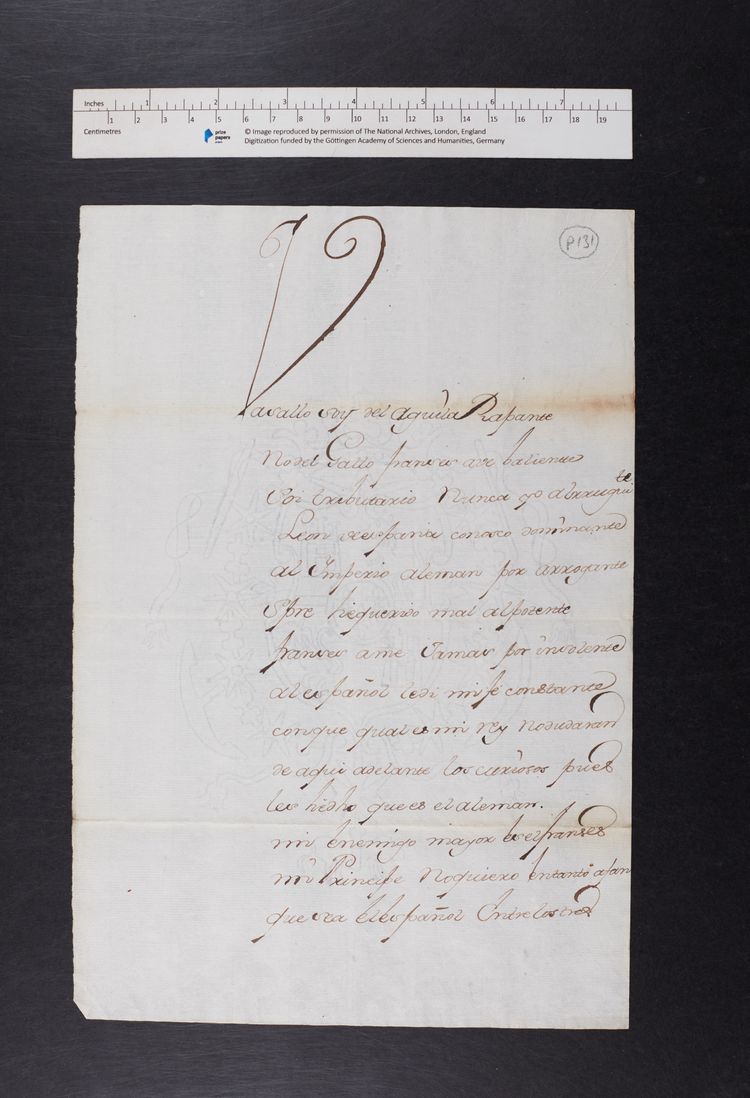

Two poems

There are two poems among the documents of La Ninfa. One of them (P0137) is a religious text that could have been used as a prayer. The other (P0131, transcription below) has political undertones. Its anonymous author expresses their love and loyalty for the king of Spain and their distaste and suspicion of France.

“Vasallo soy del águila rampante

no del Gallo francés ave valiente

soy tributario nunca yo al rugiente

León de España conozco dominante

Spre he querido mal al potente

Franses ame jamas por insolente

Al español le di mi fe constante

Conque qual es mi rey no dudaran

De aquí adelante los curiosos pues

Les he dho que es el alemán.

Mi enemigo mayor es el francés

Mi Príncipe no quiero en tanto afán”

by Alejandro Salamanca

University Institute of Florence

Contact: alejandro.salamanca@eui.eu

with the help of Marit Heinemann

The author of the case studies is responsible for the content and for image licencing. The Prize Papers Project assumes no liability.